“Excellent Result” is the headline that the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry chose for its report on global exports in June.

An interesting description for an industry that has seen the number of watches sold fall from over 24 million six years ago to under 16 million last year.

Most business leaders and analysts would consider a 33% fall in unit sales a catastrophic direction of travel.

Not the Swiss.

Of course, the value of exports has risen from CHF 18.8 billion in 2017 to CHF 23.7 million last year and the June report shows that the monthly value of exports has risen again by 14% year on year.

Excellent result?

I beg to differ.

In the years I have been reporting on the watch industry, I have never felt its products have been more attractive to consumers.

We have broken out of a situation where it was really only horological nerds who had an interest in analogue watches.

Today, I chat to family members and friends, who stopped wearing watches in their teens, about the latest Cricket watch from Vulcain or the rising prices of Aquanauts on the secondary market.

As many people down the pub will talk about mechanical watches as will have an opinion on vinyl records.

And yet the industry manages to sell fewer and fewer watches, albeit at higher and higher prices.

Is this sustainable?

My concerns are exacerbated by the way that the major manufacturing groups, in particular Richemont and Swatch Group, are behaving.

The publicly-traded behemoths’ strategy is distorted by shareholders and financial analysts who want to see quarter-on-quarter profits rising.

There are many ways to increase profits. For example, make highly desirable watches that sell like hot cakes.

But this doesn’t seem to be the route that many group brands are choosing. Instead, there is a mixture of increasing the average price of every watch and retaining more profit from every watch sold.

This may explain why Richemont proudly declares that directly-operated boutiques accounted for 68% of group sales in its 2023 financial year compared to 66% a year before.

In a red hot market, which we have observed across the Western world since the end of the first lock downs of 2020, trusting big city boutiques to deliver your sales and profits has been working in a way that satisfies shareholders and bean counters, but are the brands from major groups actually getting stronger?

I recently spoke with John Henne, owner of Henne Jewelers in Pittsburgh, who had a bit of a ding dong with Swatch Group-owned Omega about floor space and position for the brand in a hugely expanding showroom.

Omega and Tudor had been offered equal square footage in the new space, but Omega had been allocated the premier of two positions in terms of sight lines within the store and window displays.

Not good enough, Omega argued. It had to have more acreage than Tudor.

Multibrand retailers will be familiar with this sort of horse trading when it comes to allocating space, and most would have demurred to Omega because it is five times the size of Tudor in terms of turnover, and makes twice as many watches each year.

Henne, which is anchored by Rolex so may have an understandable bias to its sister brand Tudor, took the decision that it could live without Omega, which will now have no presence in Pittsburgh, a city with roughly the same population as Leicester.

My assertion is that wholesale may not be the perfect business model for every luxury watchmaker, but it is better than all the alternatives.

Omega is not alone is focusing its energy on the best possible retail presence in the triple-A locations.

Patek Philippe and Rolex, which operate almost entirely through retail partners, are doing the same.

The difference is that their retail partners are delighted to have the opportunity to invest in bigger and better stores.

These retailers, I predict, will sell more and more watches from brands that back authorised dealers, average transaction values will rise and so will profits, as we see from the UK accounts of Patek Philippe and Rolex.

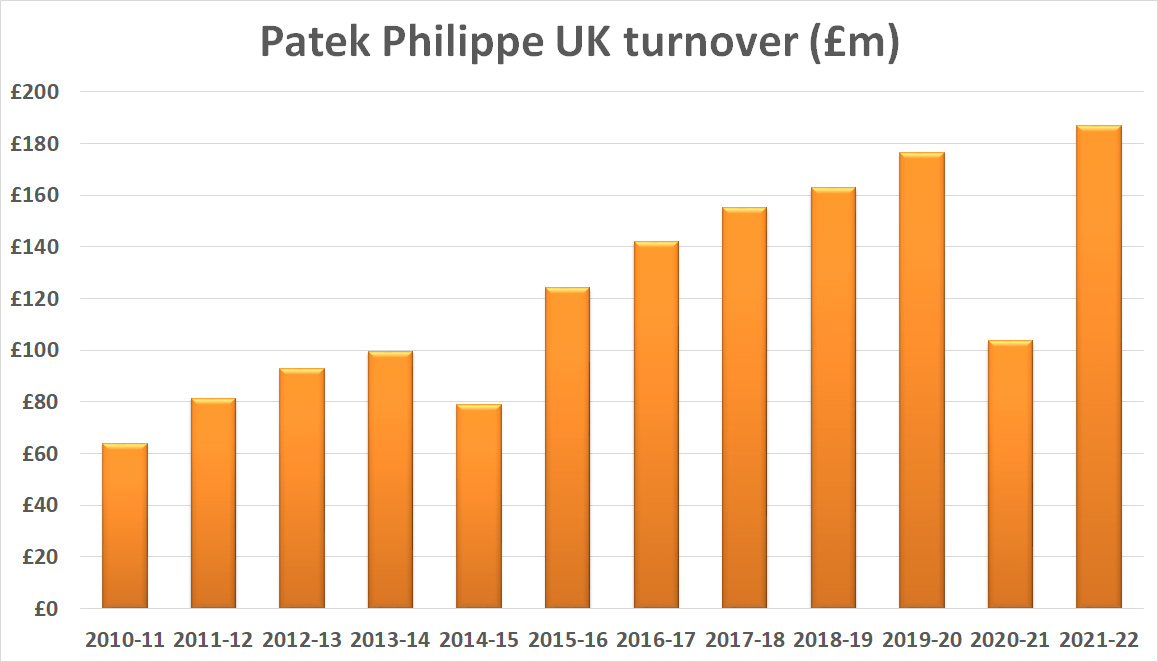

Patek Philippe’s wholesale business increased its turnover by a modest 5% from around £175 million in 2019-20, the last full year before the pandemic, to £185 million in the still covid-affected 2021-22.

Patek Philippe’s wholesale business increased its turnover by a modest 5% from around £175 million in 2019-20, the last full year before the pandemic, to £185 million in the still covid-affected 2021-22.

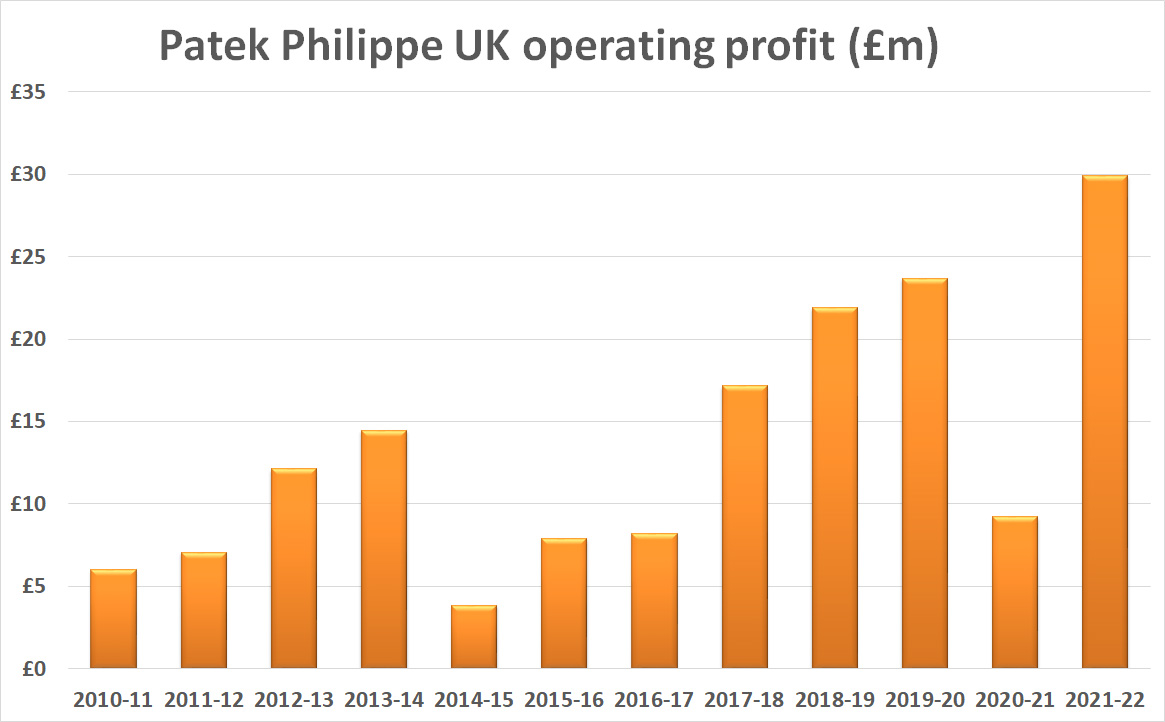

Over the same period, operating profit rocketed 25% from £24 million to £30 million.

Rolex Watch Company Ltd has quadrupled sales from 2010 to 2020 and operating profits have multiplied by 35-times.

To plagiarise Winston Churchill’s description of democratic government, wholesale may not be the perfect business model for every luxury watchmaker, but it is better than all the alternatives.

If the groups continue on a path of increasing alienation with retail partners, they will find themselves needing to sell ever-more expensive watches through a dwindling number of their own stores, and without the advantages that multi-generational family businesses, embedded in their communities, enjoy.